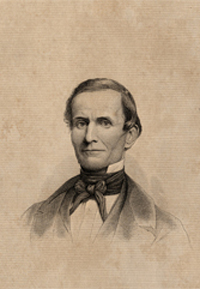

Wesleyan's Fourth President

|

Augustus W. Smith1852-1857 "There comes to your mind the memory of the critical scholarship, the gentlemanly bearing, the spotless character, which have endeared to so many the name of Smith." |

The first layman to be elected as president of Wesleyan, Augustus W. Smith was born on May 12, 1802, in Newport, Herkimer County, New York. His mother died when he was an infant, and his father moved the family to Paris Hill, approximately ten miles from Clinton, New York, where Smith eventually enrolled as a student at Hamilton College.

He graduated with highest honors in mathematics from Hamilton in 1825. Quiet and studious, he taught mathematics at the Oneida Seminary, where he was elected principal after two years of teaching. When Willbur Fisk was assembling his first faculty for the new Wesleyan University, he heard about Smith and persuaded him to join the university's faculty.

At Wesleyan, Smith was a diligent professor, respected by students and faculty alike for his intellect and his interest in helping Wesleyan become a pre-eminent institution. He chose much of the first material equipment for classrooms and for laboratories. In 1849 his textbook, An Elementary Treatise on Mechanics, was published, and remained a standard in the field for years.

Smith had served as acting president during Willbur Fisk's absence, and when Stephen Olin died in 1851, the trustees debated for a year whether a layman could be an effective university president, since Wesleyan was tied to the Methodist Church, as well as whether an academic could raise enough money for the university.

Finally, the Trustees offered the position to Smith (after first offering it to the Rev. Dr. John McClintock of the class of 1835, who later became the first president of Drew Theological Seminary).

Finances were tight at Wesleyan when Smith assumed the presidency, and he spent a lot of time traveling to raise money. Eventually, $100,000 was raised.

After several years in office, despite the respect for his scholarship, a number of trustees and students began to feel that he was not outspoken enough on issues of the day. Eager to avoid controversy, he resigned, yet his loyalty to Wesleyan kept him on campus for another year to aid the transition.

In 1859 he was appointed professor of natural philosophy at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, a chair he held until his death on March 26, 1866. Of note, his ties to Wesleyan as well as to academic administration did not cease: his daughter was later elected president of Wells College, and numerous relatives attended Wesleyan.