Molly Volker '26

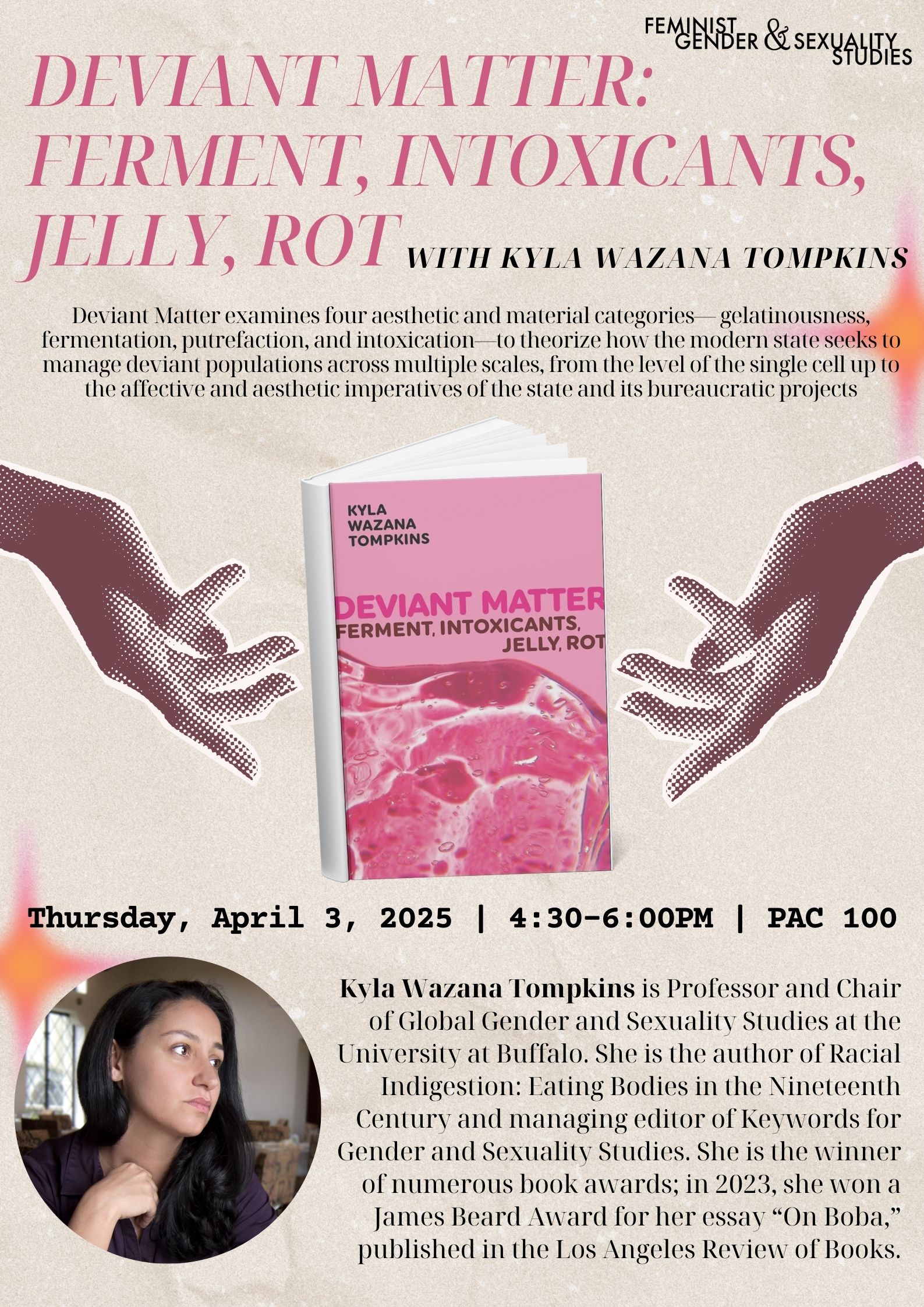

On Thursday, April 3, the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Department welcomed Kyla Wazana Tompkins, Professor and Chair of Global Gender and Sexuality Studies at the University of Buffalo, to give a talk about her new book, Deviant Matter: Ferment, Intoxicants, Jelly, Rot. Tompkins is the author of Racial Indigestion: Eating Bodies in the Nineteenth Century and managing editor of Keywords for Gender and Sexuality Studies. She is the winner of numerous book awards; in 2023, she won a James Beard Award for her essay “On Boba,” published in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Tompkins began with a meditation on the use of aesthetics as a tool of criticism–a way to bring writing “closer to its object,”–and proceeded to open the talk with an anecdote about a uniquely messy jelly sculpture she and a friend had brought to a potluck in graduate school. She discussed how this jelly sculpture and its alienation from the rest of the potluck served as a representation of the alienation that she and her friend were feeling within their academic institution. “Gelatin absorbs and makes visual and kinetic what is sometimes not describable or utterable–what is felt–but is nonetheless present in its vicinity; it makes what might otherwise be preconscious visible.” This personal anecdote set the stage for the remaining presentation–establishing the relationship between materialities and lived experience, and giving the audience a tangible account of the connection being made.

Continuing on, Tompkins investigates the ways in which materialities are taxonomized and placed in disparate categories of value, with some being marginalized, alienated, and labeled as “deviant,” particularly in conversation with the ways in which this same phenomena has been done to groups of people. She refers to “sensory histories,” and questions from where these widely-held marginalizations of certain materialities emerged. In particular, Tompkins makes reference to the connection between the materiality of ferment with the concept of labor-time, and the way that connection operated on sugar plantations as a tool of the colonial project. Ferment occurs when sugarcane juice is left to sit without processing, which would occur in-tandem with rest for those enslaved people who were working the plantations. This connection raises questions about the emergence of modern taste preferences–why is sweetness considered “good” while sourness is “bad”? Following this intervention, one might say that sweetness represents labor-time, which upholds the colonial capitalist projects that shaped the modern world. She continues to question policing regimes of hygiene–how the aesthetic of both administrative and literal hygiene are used to enforce state violence and control.

Referring particularly to concepts from Audre Lorde’s “The Uses of the Erotic,” and Cathy Cohen’s “Deviance as Resistance,” Tompkins investigates how these “deviant materialities” can serve as spaces of resistance to the oppressive status quo, and how choosing to exist in a sensory world that embraces the deviant is an act of resistance accumulates over time.

In closing, Tompkins showed images of a number of object-examples from works of art and media that gave more tangible examples of different sensory orders, and then took questions from the audience. Some of those questions included: What other objects and case studies have you worked with in the process of writing this book? Why do you think different intoxicating substances are criminalized differently? Are the ideological regulations of aesthetic experience imposed to reinforce social distinctions, or do they produce those social distinctions in the first place? Tompkins offered thorough responses to these questions, tying them back into her talk and presentation on the ordering of the senses, and the sensory histories that govern our lives.

Professor Tompkins’s talk presented a clear argument about the relevance of aesthetics in the world of criticism, and the ways in which subjugation of materiality is connected to the subjugation of people. Through personal anecdote, historical and literary references, and physical object-examples, she communicates a theory of imposed sensory organization, and the ways in which materialities, like people, are labeled as “deviant.”