HISTORY OF THE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY PROGRAM

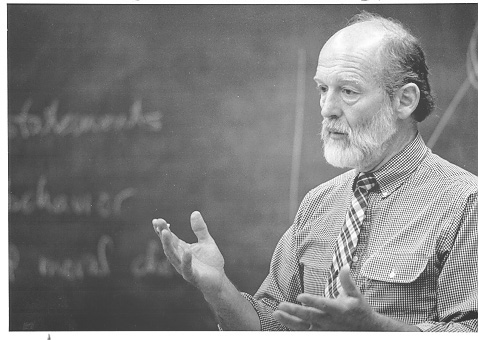

Earl Hanson,Fisk Professor of Natural Sciences

Founder of the Science in Society Program

Program Chair, 1975-86, 1991-93

The Science and Technology Studies program was founded at Wesleyan in 1975 as the College of Science in Society, with the assistance of a 5-year grant from the National Science Foundation and the Fund for the Improvement of Post-Secondary Education. Earl Hanson, then Professor of Biology, was both the author of the grant and the founding Chair of the Program.

The Program was then foreseen as a successor to the College of Quantitative Studies, a three-year interdisciplinary major in science and applied mathematics, which had been active from 1960 until 1966. The College of Quantitative Studies had been organized as one of three alternative "colleges" within the University (along with two still extant programs, the College of Letters and the College of Social Studies). Intended to foster interdisciplinary, applied work within the sciences, the College was especially notable for its student projects, involving the solution of problems for outside agencies like Raymond Engineering and the Department of Motor Vehicles, and for its Senior Seminar, an interdisciplinary capstone course including the sciences, philosophy, and public affairs.

Like many "Science, Technology, and Society" or "Science, Techology, and Values" programs being developed at roughly the same time at a number of engineering schools (notably MIT, Lehigh, Renssalaer, Virginia Tech and Georgia Tech), but adapted to the context of a selective liberal arts university, the original Science and Technology Studies program aimed to encourage a humanistic approach to scientific and technological problems, conjoined with a commitment to scientific excellence and a recognition of the scientific and technological dimensions of many social and political problems. Students initially went through their three years in the Program in a sequence of small Colloquia with all other students in their cohort, while taking additional courses tailored to their particular interests. The capstone of the Program in its early years was a required thesis, which students typically worked on for up to two years, and a Senior Colloquium in which students presented their thesis research and other current issues in a seminar format. Although the topics for these thesis projects were quite wide-ranging, environmental issues, critical assessments of medical theory and practice, agriculture, urban planning, and human population growth were common foci of student research.

Apart from the founder, Earl Hanson, the initial staffing of the Program was drawn from faculty whose time was borrowed from other departments (notably C. Stewart Gillmor in History and Barry Gruenberg in Sociology) and from faculty hired on term contracts with funding from the initial grant to the University (including science writer Jeffrey Baker, planner Howard Brown, writer Barbara Bell, and historian Howard Bernstein). In 1979, the University confronted the difficult decision whether to establish the Program on a permanent basis after the expiration of its outside funding, at a time in which the University as a whole was reducing the size of the faculty. After extensive Committee review and faculty debate, the University decided to commit three faculty FTE to enable the Program to continue, with the expectation that these positions would be filled by six or more faculty holding joint appointments between the Program and other departments in the University (including Earl Hanson, whose appointment was officially converted to a joint appointment in Biology and Science in Society). The conversion of the original term appointments to joint tenure-track or tenured appointments began in 1981, with the appointment of Joseph Rouse in Philosophy and Science in Society. Over the next decade, other appointments were added, including Karen Knorr-Cetina (Sociology), Drew Carey (Earth and Environmental Sciences), Sue Fisher (Sociology), Anthony Daley (Government), and Marc Eisner (Government). Robert Wood (Government) and William Trousdale (Physics) also joined the Program for extended periods during the 1980's. Robert Rosenbaum, Professor of Mathematics and founder of the College of Quantitative Studies, rejoined the Program for one year as Chair when Earl Hanson was on leave. Many of the faculty who had been hired under the original grant continued to teach in the Program during this extended transition; Howard Brown, the last of the original adjunct faculty who had begun the Program, left the University in 1990.

Several significant intellectual and pedagogical trends are discernable in the Program's development from 1980 until 1993, during which time the Program typically graduated between 10 and 15 students a year. The social sciences took on a more prominent role in the Program, which had originally been conceived primarily by natural scientists: most notably influential were the newly emergent interdisciplinary social studies of science, and political economy and policy analysis. Traditionally structured academic courses in these fields took on a more prominent role in the curriculum, replacing many of the relatively free-wheeling, project-oriented colloquia. While independent research projects remained a prominent part of the Program's requirements, these were gradually scaled back from 2-year to 1-year projects, and some students were permitted to substitute a briefer senior essay for the senior thesis. The Program itself formally changed from a three-year "college" to a two-year interdisciplinary major, a change which also eliminated comprehensive oral and written examinations in the junior and senior years. Although there was no formal division within the Program, students increasingly tended to gravitate toward one of two distinct intellectual foci: critical philosophical and sociological reflections upon the sciences and/or medicine, and environmental studies, especially environmental policy. Many Program faculty converted their joint appointments back to traditional departmental positions, while continuing to teach in the Program.

The untimely death of Earl Hanson in October 1993 precipitated a substantial reorganization of the Science and Technology Studies program. Not only was Professor Hanson the founder, the Chair, and the faculty member most prominently associated with the Program; his interests provided the primary link between the two distinct "wings" of the Program in environmental studies and interdisciplinary science studies. Because of his many contributions, and deep commitment to the Program, it was widely recognized that no single faculty member could replace his role in the curriculum and administration of the Program.

After extensive discussion, a decision was made to split the Program. A new certificate program in Environmental Studies was organized under the leadership of faculty in Earth & Environmental Sciences, Economics, and History, while the Science and Technology Studies program itself continued with a more specific focus upon the history, philosophy and social studies of science and medicine. With the aid of a substantial grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Science Foundation through their joint initiative on "Science and Humanities: Integrating Undergraduate Education," continuing faculty Joseph Rouse and Sue Fisher were joined by Professors C. Stewart Gillmor, Jill Morawski, and William Johnston. Half a dozen new courses were developed under the auspices of the NSF/NEH grant. By splitting off environmental studies into a separate course of study, the Science in Society Program was able to expand its science requirements, add a substantial curricular component in the history of science, and provide its students with a more intellectually coherent major. After a brief interregnum while the new curriculum was being developed, the first students graduated under the new requirements in 1995, and the Program has once again grown to include over 30 junior and senior majors, making it one of the five largest interdisciplinary majors at Wesleyan University. The appointment of Assistant Professor Jennifer Tucker (History and Women's Studies) in 1998 strengthened our core faculty, and marked the consolidation of the revised curriculum as a vital component of Wesleyan's overall program of study.

The Science and Technology Studies program holds a distinctive and important place in the context of Wesleyan University's mission. Wesleyan aspires to combine the forefront research typical of the best universities with a commitment to the intensive undergraduate teaching that characterizes the best liberal arts colleges. Such a joint commitment would be impossible to fulfill without making the best of current research accessible to undergraduates in the classroom. Throughout its first quarter century, the Science in Society Program has been guided by this goal, adapting the most innovative and informative research on the social, cultural, and political significance of the sciences to the undergraduate classroom. Moreover, since Wesleyan's Ph.D. programs in the sciences are the most visible and distinctive manifestation of the seriousness of the University's commitment to research, our Program's aspiration to connect the best humanistic and social scientific studies of the sciences and medicine with serious and sustained study of a science undertaken with Wesleyan's research-oriented science faculty is central to this University's self-understanding.