Wesleyan's First Women

Founded as a men's college in 1831, Wesleyan may be unique in its first round of coeducation, which began when women were first admitted in 1872 and ended when this policy was rescinded in 1909.

According to David B. Potts' Wesleyan University, 1831-1910 (Yale, 1992), the 1872 decision to admit women stemmed from Wesleyan's identity as a Methodist institution. In accordance with "Methodism's well established practice of educating young men and women together" (p. 101), this decision also reflected the efforts of five important trustees, most importantly Orange Judd, for whom Judd Hall is named. By the 1860s and 1870s Methodism had begun to consider ordaining women as ministers, and newly established Methodist institutions like Boston University, Syracuse University, and Vanderbilt University were, from the start, founded as coeducational institutions at around this time. It was thus logical to consider coeducating Wesleyan, as well. A second important impetus lay in proposals to coeducate at seven New England institutions, all of which were initiated in 1871. Though not formally coordinated, these were somewhat interrelated, and all owed something to the women's suffrage movement of the early 1870s. For example Henry Ward Beecher, a figure in that movement, proposed coeducation to Amherst's trustees in 1871, but his proposal was turned down.

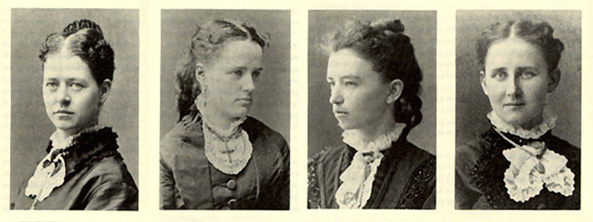

Wesleyan's first women were the four female members of the class of 1872: Jennie Larned, Phebe Almeda Stone, Angie Villette Warren, and Hannah Ada Taylor (see picture). A brave and mutually supporting group, these women faced formidable problems, among them that the college provided no campus housing for women until 1889, and rooms elsewhere in Middletown were not initially available to women. Yet all four were outstanding students. They not only graduated on schedule but received highest academic honors. From 1872 until 1892, women remained a tiny minority of the undergraduate community. In all only forty-three women were graduated between those years. Many of their male fellow students received them cordially, but the overall climate was far from welcoming; and most male undergraduates claimed that the women "though with us are not of us." (p. 104) Upon graduating, most followed the mores of the time which forced women to choose between marriage and a career. Of the forty-three who graduated, twenty-three did not marry and went into careers, usually in teaching. The other twenty married, and most stayed at home.

The shift away from coeducation was sparked by a change in the leadership of the trustees. Trustee Stephen Henry Olin (son of President Stephen Olin, 1842-51) was the leading spirit behind Wesleyan's progress away from Methodism and its redefininiton as a metropolitan-based university, with heavy emphasis on athletics. This shift would align Wesleyan more closely with the values of Amherst, Williams, Yale and all-male institutions. Somewhat contradictorily, however, women's admissions were increased in 1898, and male admissions decreased accordingly. This development fueled the fears of those who held that women's presence at Wesleyan was curtailing opportunities for males.

Potts' history emphasizes the growing signs of discrimination against women in the wake of these developments. Student publications soon began to exclude women, and women's names and organizations were not entered into Wesleyan's yearbook after 1898. Women were neither allowed into the new gymnasium, to which they had contributed, nor allowed to sit with the senior men at commencement during these years. Some of these negative developments might have eventuated in a separate women's college within the university, on the order of Pembroke College at Brown; but the net effect was discriminatory when that movement failed to get off the ground. Still worse must have been the more informal types of discrimination, which included verbal harassment and graffiti. Nevertheless, women made a comfortable home for themselves in Webb Hall, their new dormitory at the site of the current power plant, which Wesleyan acquired in 1889; and they developed a rich literary and social culture that reached out to alumni, as well as undergraduates.

The first decade of the twentieth century dealt coeducation its final blow. The lead cause was a decline in Wesleyan's overall admissions, which most blamed on fears that the school had become too feminized and might follow the sorry example of Boston University, where the undergraduate population was dominated by women. Starting in 1900, the admission of women was capped at 20%, but this measure never fully reassured coeducation's enemies. The trustees' decision to end coeducation in 1909 can be seen in retrospect as a nearly inevitable culmination of tendencies that had been set in motion long before that time. It was hailed in student publications, one of which asserted:"The Barnacle is at last to be scraped from the keel of the good ship Wesleyan!" (p. 219) Last-ditch efforts to found a separate college for women gained momentum in 1907, but they failed to generate the necessary revenue, and the effort was abandoned before long. Under the leadership of Elizabeth C. Wright, '97, a committee was formed to consider other options. This effort eventuated in the founding of Connecticut College for Women, which opened in New London, CT, in 1915.