Q&A

Q: Your book, A Sacred Space is Never Empty: A History of Soviet Atheism, was recently published and explores the theme of atheism and communist ideology in the Soviet Union. Can you tell the Wilson Center audience more about this book and what you hope readers take away from it?

A: I think the first thing worth underscoring is that A Sacred Space Is Never Empty is the first history of Soviet atheism from the 1917 revolution to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 that is grounded in archival sources. This is worth noting, and should surprise us, because the binary opposition of godly West and godless communism defined the Cold War – and yet there was little attention paid to the “godless” part of this term. The meaning of Soviet atheism was largely implicit, and was also perceived to be stable and unchanging. In my book, I tried to destabilize these assumptions. My point of departure was to take Soviet atheism seriously on its own terms, to understand its meaning and function in the broader Soviet project, and to assess whether it lived up to the expectations and hopes that various parties placed on it over time.

I hope the readers take away at least two things from the story of Soviet atheism. First, for understanding the Soviet project, I think that atheism mattered, even if the participants in the political project did not always take its “religious” component seriously. I think atheism’s role in the Soviet project – which, I argue in the book, is a tool for contesting competing claims to political, ideological, and spiritual authority – can tell us a great deal about how Soviet Communism was imagined and experienced. Second, a study of Soviet engagements with religion and atheism is necessary for understanding the transformations of religious and spiritual life in the modern era, in the USSR but also beyond it. I think the Soviet atheist experience has some lessons that remain relevant, and these lessons have not yet received the attention they deserve.

Q: Your work at the Wilson Center and beyond has been critical in developing a more complete history of religion in a communist country. Can you discuss the importance of the role of atheism in the Soviet Union?

A: The book shows that, despite its monopoly on ideology and power, the Soviet Communist Party never succeeded in overcoming religion and creating an atheist society. Instead, engagements with religion transformed atheism itself, showing Soviet atheists that exorcizing religion was not enough, and that to overcome it, they had to produce positive beliefs, practices, and spiritual commitments; that their goal was not just the absence of religion, but atheist conviction. I argue in the book that even with its new understandings and approaches, Soviet atheism never managed to fill the “sacred space” at the heart of Soviet Communism, but it nevertheless left an imprint on Soviet society. Soviet society did indeed become more secular by the 1960s, though atheist work was not the only, or the main, reason for this transformation. Indeed, what’s interesting is that some of the societal patterns that Soviet atheists observed in the 1960s and 1970s – the spread of religious and ideological indifference, on the one hand, and the rise of religious dissent and new religious movements on the other – could be observed in Western societies as well (the historian Hugh McLeod’s has a very illuminating analysis of this in his book, The Religious Crisis of the 1960s), suggesting that these transformations were caused by larger structural causes rather than ideological campaigns. What is important, to my eyes, is the political meaning of Soviet atheism and the role it played in the broader logic of the Soviet project. In the late 1980s, when the regime found itself in crisis, Mikhail Gorbachev abandoned atheism and returned religion to Soviet public life, putting in question the moral and political legitimacy of the Soviet Communist project. What I suggest in my book is that there was a relationship between the two divorces that took place in the Soviet Union’s final years—the divorce of Communism from atheism, and the divorce of the Soviet state from the Communist Party.

Q: Religion has become more prevalent in former Soviet states such as Russia, Ukraine, and Georgia after the fall of the Soviet Union. Can you tell the Wilson audience how religion in the former Soviet states has changed since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989?

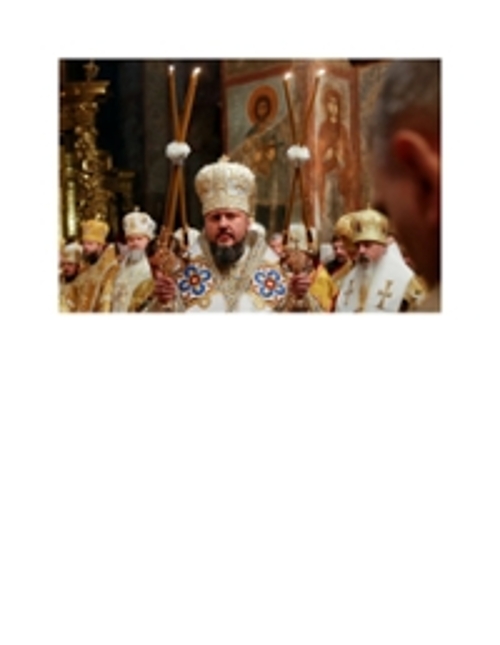

A: I begin and end A Sacred Space Is Never Empty with an event that I think helps us understand the genealogy of the more prominent role of religion in former Soviet states following the Soviet collapse. This event is the celebration of the Millennium of the Baptism of Rus in 1988, which commemorated the decision by Grand Prince Vladimir of Kyivan Rus’ to adopt Christianity in the year 988. The celebration of the Millennium – because it was acknowledged at the top, reframed as a legitimate part of the country’s history, and celebrated in public - transformed the relationship of both the party and the state to religion and atheism. To put it most directly, religion was no longer cast as a backward “holdover” marginal to Soviet life, but was reframed as a legitimate part of the country’s history. As Gorbachev put it during his meeting with Patriarch Pimen of the Russian Orthodox Church in advance of the celebrations, the Millennium would be commemorated “not only in a religious but also a sociopolitical tone, since it was a significant milestone in the centuries’ long path of the development of the fatherland’s history, culture, and Russian statehood.” He also stated that religious believers were “Soviet people, working people, patriots,” and, as such, entitled to all the rights of Soviet citizenship “without restrictions” – including “the full right to express their convictions with dignity.” These statements, in another context, would not be considered particularly remarkable, but in the Soviet context they were radical, because tacitly acknowledged that for the entire Soviet period, religion had not been considered a significant part of the country’s history, and believers had not been treated as full citizens or allowed to “express their convictions with dignity,” even though the Soviet Constitution had always formally guaranteed them these rights.

The return of religion to politics and public life in 1988 broke the links between atheism and the Soviet state, and can be seen – in my view – as the entry of the Soviet Communist project into its final chapter: dissolution. The argument has been made that without the party was the only institution that unified the republics of the USSR into a coherent whole that was larger than the sum of its parts. Atheism, I think, was a constituent part of this framework in that it was intended to undermine the political, ideological, and cultural legitimacy of local religious institutions and traditions, reorienting local ethnic and national identities toward the greater identity of the “Soviet people.” By discarding atheism, the various national projects of the USSR’s constituent republics could be buttressed by religious institutions, histories, and identities. In the late Soviet context – and especially during perestroika, when the “Soviet” had been depleted of its moral legitimacy – religious institutions could enter the public sphere with the claim that they represented the authentic histories, identities, and interests of the nationalities still formally under Soviet power.

This moment opens a new era not just in (post-)Soviet religious life but also in (post-)Soviet politics. In Russia, the celebration of the Millennium in 1988 is called “The Second Baptism of Rus,” and in a 2013 documentary of that title on the television channel "Rossiia-1", which aired occasion of the 1025th anniversary of Grand Prince Vladimir's conversion of the people of Rus' in 988, this narrative was laid out for the view in a straightforward story about the return of Orthodoxy to Russian public life following seven decades of Communism as a story of the Russian people, and the Russian nation, returning to their authentic spiritual foundations after a troubled period of political repression and ideological confusion. The Soviet past, then, is reframed as a story of continuity rather than rupture. In his interview for the documentary, President Putin explains that the Communist moral code, the so-called “Moral Code of the Builders of Communism” that was introduced in 1961 – incidentally, during Nikita Khrushchev’s antireligious campaign – as a constituent part of the broader project of “Building Communism,” was basically grounded in religious moral principles, and that when this moral code “stopped existing” in the late Soviet period, a “moral vacuum” formed that could only be filled by one thing: “true, real” religious values. The return of religion to Russian life, then, is cast as an organic social process rather than a constructed political project. As Putin puts it, "people, in essence, converted of their own accord to their roots and spiritual values, which was the natural rebirth of the Russian people (russkogo naroda).” I think the erection of a giant statue to Grand Prince Vladimir in the center of Moscow in 2016 is, in some ways, the explicit expression of an ideological project that had been implicit throughout the post-Soviet period – a project that has its origins in the celebration of the Millennium of the Baptism of Rus’ in 1988.

I think we see some version of this reframing of the relationship between religion and politics in other post-Soviet republics, including Ukraine and Georgia, although of course the path this new ideological project takes in each country depends on numerous structural and contingent factors: the relationship of religious institutions to the local conceptions of nation and state most obviously, but also political relationships, demographic factors, and the relationships with near and distant neighbors. In Ukraine, for example, we see a very different process playing out: from a fairly stable period of disestablishment and robust religious pluralism to a project, undertaken in the last two years, to establish a national church carried out with the participation of the secular Ukrainian state.

Q: What’s next for you? Do you have any upcoming projects or future plans you can tell us about?

A: A Sacred Space Is Never Empty ends by showing that the political significance of religion's return to Soviet life was a blind spot for the Soviet Communist Party. But, perhaps more surprisingly, it was also a blind spot for Western observers who had been fighting for religious rights behind the Iron Curtain for decades. My second book project, titled “The Crusade Against Godlessness: Religion, Communism, and the Cold War Order,” emerged from a puzzling disconnect between perception and reality: on the one hand, the foreign perception of Soviet religious affairs was that the Soviet state was committed to an aggressive atheist program, while inside the USSR, on the other hand, religious policy and atheist work were much more ad-hoc, ideologically inconsistent, and politically pragmatic. In my second book, I try to connect and make sense of these two seemingly contradictory narratives.

In some ways, then, “The Crusade Against Godlessness” is both a continuation and a mirror image of A Sacred Space Is Never Empty. It continues and develops the story told in Sacred Space in two ways in particular: first, by de-centering Russian Orthodoxy and turning our attention to other religious groups in the USSR, and especially to those groups who had, to borrow the Soviet terminology, “co-religionists” abroad (from Catholics and Protestants, to Jews and Muslims, to Baptists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Seventh-Day Adventists); and second, by looking at the religious question in Soviet international relations and foreign affairs. So, whereas A Sacred Space Is Never Empty focused on internal developments in the USSR and the ways in which atheist ideology shaped, and was in turn shaped by, engagements with religion at home, “The Crusade Against Godlessness” turns our attention to Soviet engagements with religion abroad, and looks at how these shape the regime’s perceptions of religion’s role both inside the USSR and on the global stage.

The return of religion to politics and public life at the end of the twentieth century is one of the most unexpected developments in modern history, yet explanations for religion’s return have thus far focused on globalization and the rise of fundamentalism, largely ignoring the Cold War context, and the Soviet side of the story in particular. This project explores the international and transnational dimensions of modern religious politics, offering a new genealogy of religion's return that shows the ways in which this process was entangled with the perceived threat of communism and atheism. Over the course of the twentieth century, and especially during the Cold War, religion and communism were engaged in what both sides perceived to be an existential conflict. This made Soviet believers the subject of much attention among many different religious and social groups, yet the significance of this struggle for both the making and unmaking of the Cold War order has not yet been analyzed. How and why did religion “return” – both within the Soviet Union and across the globe (and had it really gone away)? What role did transnational religious mobilization play in the consolidation of the Cold War order? Conversely, in what ways did the Cold War struggle with “atheistic communism” inform the ideas and activities of religious organizations and believers? “The Crusade Against Godlessness” examines these questions by looking at religious organizations as significant political actors that shaped religion, Communism, and the Cold War on both sides of the Iron Curtain.