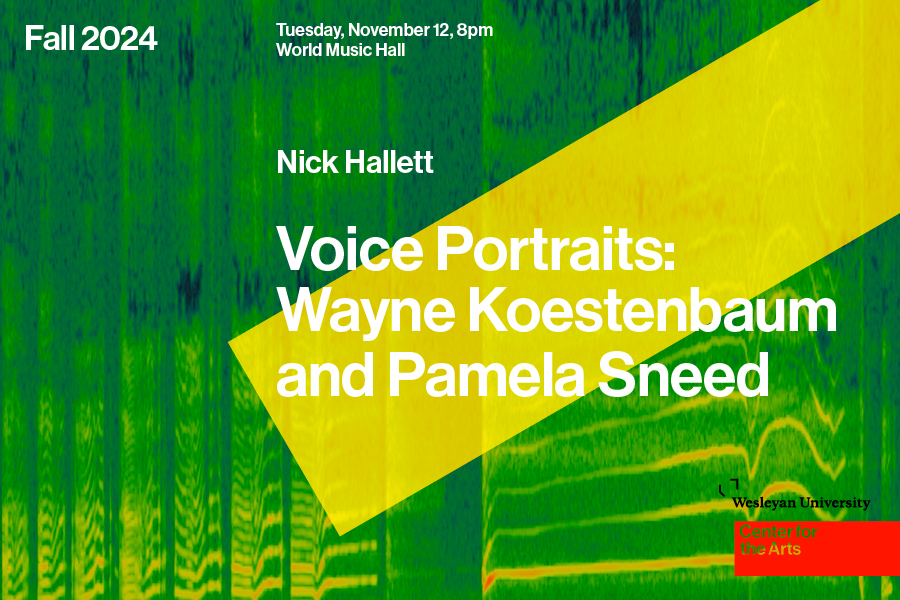

Graduate Recital: Nick Hallett—Voice Portraits: Wayne Koestenbaum and Pamela Sneed

Tuesday, November 12, 2024 at 8:00pm

World Music Hall

Free and open to the public

Graduate music student Nick Hallett debuts a series of multichannel electronic works that capture the sonic likenesses of celebrated poets Wayne Koestenbaum and Pamela Sneed.

PROGRAM

- Wayne Koestenbaum

- “Child’s Destiny,” Daisy Press, vocals

- Pamela Sneed

Smooshing the sound-object and the object-voice together into a square

The principle of Acousmatics, that separating sound from source creates new listening experiences, has driven the evolution of the electronic music studio from its beginnings with the research of composer Pierre Schaffer in postwar France to the contemporary DAW. The Studio d’Essai, one of the first tape studios, brought forth ways for reconfiguring sonic materials that continue to expand human consciousness. Schaffer used the term sound-object (objet sonore) to describe the results of a field recording altered by technology. While the invention of the phonograph many decades earlier was to archive telephone conversations, the first moods to capture the attention at Studio d'Essai were the fast-loud sounds of industrial machines and warcraft, giving light to Musique Concrète.

In the realm of words, Concrete Poetry developed around visual forms, namely the alphabetic letters used to signal sounds, not the sounds themselves, around which onomatopoetic recitation emerged as a revolutionary act. Also from postwar France, Ultra-Lettrism subverted the use of the tape recorder as an extension of poetry. Dispatched with smaller budgets than electronic composers, Henri Chopin and François Dufrêne rendered their concrete poems into states of euphoric madness and horrendous disfigurement—the voice as sound-object. Living under French colonial rule in 1940s Martinique, the poet and politician Aimé Césaire wrote, “modern science is perhaps only the pedantic verification of some mad images spewed out by poets…Poets have always known.”

In his book A Voice and Nothing More (2006), philosopher Mladen Dolar borrows a term from psychoanalytic theory, object-voice, to explore aspects of communication that do not contribute to meaning within linguistics, metaphysics, paralanguage (i.e. hiccups, inflection), and even singing, but stops short of acknowledging intentional nonsense, concrete poetry, and musical improvisation. While Schaffer’s electronic sound-object gives way to new modes of listening, Dolar (not to mention Lacan) leaves voluntary play outside the object-voice’s reach.

This is ironic. Acousmatic listening to the object voice is possible when the body from which it emerges remains unseen. Pierre Schaeffer’s derives the term acousmatic from the ancient Greek Pythagoreans, who were divided into two sects. The most advanced, mathēmatikoi (“learners”) espoused Pythagoras’ computative theories (including harmonic analysis), while akousmatikoi(“listeners”) were more or less initiates. They sat in silence with rapt attention to the philosopher’s lectures, as he spoke to them from behind a curtain. The unseen face of Pythagoras heightened and focused the dissemination of ideas as pure vocality. Acousmatics originates with the naked voice and the passing down of knowledge. Where do the sound-object and object-voice meet? Let’s draw the curtain and find out.

Portraiture, the transmission of a physical likeness onto a flat surface with a paintbrush or the tools of photography, constitutes an archive. Its formality suggests something official and/or intimate, that the portrayed subject holds importance to the artist or its commissioner. The artist’s hand and subject’s nature contribute equally to the work. We don’t need to pay attention to the bodies of white men on the canvases hung in Olin to understand that they hold institutional power. Kehinde Wiley’s portraits reconfigure the display of Black bodies within the Museum Industrial Complex. The public value of a celebrity increases in front of Annie Leibowitz’s camera (and perhaps decreases in front of Wolfgang Tillmans’). The best portraits look back at us, with slowly shifting eyeballs. Francis Bacon and Glenn Brown present likeness as abstraction. A portrait reveals more than the surfaces of its subject’s face, body, and wardrobe.

The idea of a Voice Portrait coalesces here. Can electronics bring the sound object and the object voice together? Can knowledge be passed down through the object voice? Can human likeness be conveyed by the voice alone? Can I make a painting of your voice?

My first portraits are of Wayne Koestenbaum and Pamela Sneed. Both are poets, authors, performers, visual artists, and teachers. Music is a big part of their practices, but they are not working musicians. They were also my voice students. We share spaces of knowledge and warmth around what they are singing and making, and how I can help them take it to the place they want it to live within their practices. I also asked Wayne and Pamela because their voices tell stories of being queer writers living through the height of the AIDS epidemic. Wayne’s voice takes us to the opera. Pamela’s voice takes us to church. I think of the portraits as archives of their voices and their stories of this time period.

The portrait sitting involves creating a casual atmosphere around a microphone. In advance, I tell the artist to bring some poems and songs. When the recording starts, I give them a series of creative prompts, many based on warmup exercises, so that their voices are at their best. Multiple vocal acts are constructed around the same poem. In between singing and reading, we have conversations. With a recording of their object-voice in hand, I go into my DAW and make sonic objects out of them. Stockhausen did it with Song of the Youths (1956). I have made a structured electronic collage out of a voice I love. It’s a portrait in an institutional space. You are looking at it.

I recorded Wayne’s portrait in August 2022 and did a study in spring 2023 for Professor Kuivila’s Sound Systems and Chamber Electronics course. Pamela’s was recorded in October 2024 and includes an arrangement of a song written in collaboration with Mazz Swift and Natalie Greffel MA ’23 for a performance at the NYC AIDS Memorial in June 2023, based on a text of Essex Hemphill, “Hold Tight Gently.”

In between the two portraits will be a different kind of vocal-electronic piece I’ve written for an upcoming album by the singer Daisy Press, called “Child’s Destiny.”

—Nick Hallett

For information about other concerts by graduate music students, visit the Graduate Contextual Concerts series page.